High Performance Habits

Chapter Excerpt: Performance Necessity

Some background information before the excerpt….

Hopefully by now, you’ve heard I have a new book coming out. It’s called High Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become That Way. It comes out September 19th, but is available for pre-order with some AMAZING bonuses right now… you can get the deluxe audibook, a professional performance assessment, and a four-hour LIVE training with me for free when you pre-order here now.

I always try to give you guys a sneak peek, so please enjoy the description, and a free chapter below!

This is the most important book of my career. I spent three years and almost a million dollars in conducting the research. It’s likely the largest study of high performers ever done, if one considers the number of people we surveyed, the depth of the interviews, the vast worldwide data set we have on our personal development students and clients, and the decade of my own professional insights as the world’s leading high performance coach and trainer that informed the work. It’s incredibly comprehensive. Still, it’s readable – my most personal book yet.

The vignettes, research and totally-doable practices will help you become even more extraordinary in your personal and professional life.

The chapter below is called NECESSITY, and it’s a big reason high performers excel across situations and domains. Enjoy!

— Brendon

ABOUT THE BOOK

Summary of High Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become That Way by Brendon Burchard

After extensive original research and a decade as the world’s highest-paid performance coach, Brendon Burchard finally reveals the most effective habits for reaching long-term success. Based on one of the largest surveys ever conducted on high performers, it turns out that just six habits move the needle the most in helping you succeed. Adopt these six habits, and you win. Neglect them, and life is a never-ending slog where plateaus, distractions and emotional turmoil are the norm.

We all want to be high performing in every area of our lives. But how? Which habits can help you achieve long-term success and vibrant well-being no matter your age, career, strengths, or personality? To become a high performer, you must seek clarity, generate energy, raise necessity, increase productivity, develop influence, and demonstrate courage. These are the personal and social habits that are proven to help you excel. This book is about the art and science of how to practice these proven habits.

If you do adopt any new habits to succeed faster, choose the habits in this book because they are statistically more powerful than almost 100 other habits. Anyone can practice these habits and, when they do, extraordinary things happen in their lives, relationships, and careers.

Whether you want to get more done, lead others better, develop skill faster, or dramatically increase your sense of joy and confidence, the habits in this book will help you achieve it. Each of the six habits is illustrated by powerful vignettes, cutting-edge science, thought-provoking exercises, and real-world daily practices you can implement right now.

HIGH PERFORMANCE HABITS is a science-backed, heart-centered plan to living a better quality of life. Best of all, you can measure your progress. A link to a professional assessment is included in the book for free.

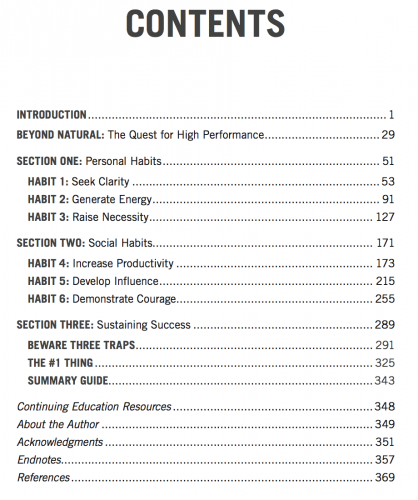

Table of Contents for High Performance Habits: How Extraordinary People Become that Way

FREE CHAPTER FROM HIGH PERFORMANCE HABITS BY BRENDON BURCHARD.

The following excerpt is from page 127 of High Performance Habits by Brendon Burchard. Used with permission. (c) 2017 High Performance Research.

“What else could I do?” The three Marines sitting around Isaac nod as a waitress refills their coffees.

I ask, “You didn’t have a choice?”

He laughs. “Well, there’s always choice. Right about then I had three choices: Sh*t my pants. Run away. Or be a Marine.”

I laugh harder than anyone at the table. The other guys are used to this kind of thing.

I ask him, “What did you say to yourself as you ran toward the explosion?”

Isaac was on foot patrol when one of his platoon’s vehicles hit an improvised explosive device. The explosion knocked him down and out. When he came to, he saw the vehicle smoldering, engulfed in a spiral of smoke, and taking enemy re. That’s when he started run- ning toward it.

“You just think you don’t want any of your guys to die. That’s all you really think: about the guys.”

Isaac stares out the café window, and no one speaks. For a moment, everyone seems lost in his own stories.

“Sometimes,” Isaac continues, “everything you are comes into play in a moment. It was just a few minutes. I can remember it like it was a two-hour movie. It’s like your whole life and all that you stand for meets the needs of a moment.”

He looks down to his wheelchair. “It just didn’t end like I thought it would. I’m useless now. It’s over.”

Isaac may never walk again. He’s a hero for providing the cover and action that helped evacuate one of the survivors of the blast. He was shot just as they got the injured survivor, one of his close friends, to safety.

One of the other marines at the table scoffs. “It’s not over, man. You’ll recover. You’re going to be just fine.”

Isaac huffs back. “Do you even see me? I can’t help myself. I can’t serve my country. What’s the point?”

His friends look to me.

“You’re right,” I say. “There is no point—unless you choose to make one. Either the point of your pain is to say to the world, ‘This is how I’ve chosen to deal with this: by giving up.’ Or the point is to show yourself, your fellow marines, and the world that nothing will stop you or the spirit of service in you.”

My words land flat. Isaac just crosses his arms. “I still don’t see the point.”

One of his friends leans in. “And you never will. If you don’t have a reason to be, man, you’re done. But the deal is, you choose the reason. You don’t have to get better. Or you choose that you must get better. It’s up to you. One choice sucks and makes your life miserable forever. The other gets you out of bed.”

Isaac murmurs, “Why try?” then remains quiet. It’s that silence no one wants to be a part of, watching someone on the edge, unsure whether to give up or live.

After a while, it becomes clear he doesn’t feel he needs to make a choice at this moment. I can tell it’s frustrating his friends. Indecision is not something marines do well. Finally, one puts his face just inches from Isaac’s and looks at him with an intensity only a military man can get away with.

“Because, damn it, Isaac, you don’t have any other choice. Because you’re going to obsess about your recovery the same way you trained infantry: like a marine. Because your family is counting on you! Because we’re here for you but we won’t accept excuses. Because a warrior’s destiny is greater than his wounds.”

#

I share this story to illustrate a rather uninspiring truth: you don’t have to do anything. You don’t have to show up for life, for work, for your family. You don’t have to climb out of bed on a tough day. You don’t have to care about being the best you can be. You don’t have to strive to live an extraordinary life. And yet, some people do feel they have to. Why?

The answer is a phrase that explains one of the most powerful drivers of human motivation and excellence: performance necessity.

Will Isaac get better physically? In many ways, it’s up to him alone. The doctors have said he may walk again—if he works hard for it. There are no promises, they tell him, but there is a possibility. Will he get better emotionally? Again, it’s up to him. He has plenty of support around him. But lots of people who need it are offered support and don’t take it. The only difference lies in whether someone decides it is necessary to get better. No necessity, no consistent action.

Necessity is the emotional drive that makes great performance a must instead of a preference. Unlike weaker desires that make you want to do something, necessity demands that you take action. When you feel necessity, you don’t sit around wishing or hoping. You get things done. Because you have to. There’s not much choice; your heart and soul and the needs of the moment are telling you to act. It just feels right to do something. And if you didn’t do it, you’d feel bad about yourself. You’d feel as though you weren’t living up to your standards, meeting your obligations, or fulfilling your duties or your destiny. Necessity inspires a higher sense of motivation than usual because personal identity is engaged, creating a sense of urgency to act.

This “heart and soul” and “destiny” stuff might sound woo-woo, but it’s often how high performers describe the motivation behind many of their actions. For example, in my interviews I often ask high performers why they work so hard and how they stay so focused, so committed. Their responses often sound something like this:

- It’s just who I am.

- I can’t imagine doing anything else.

- This is what I was made to do.

There’s also a sense of obligation and urgency:

- People need me now; they’re counting on me.

- I can’t miss this opportunity.

- If I don’t do this now, I’ll regret it forever.

They say things like what Isaac said: “It’s like your whole life and all that you stand for meets the needs of a moment.”

When you have high necessity, you strongly agree with this statement:

“I feel a deep emotional drive and commitment to succeeding, and it consistently forces me to work hard, stay disciplined, and push myself.”

People who report strong agreement with statements like this score higher on the HPI in almost every category. They also report greater confidence, happiness, and success over longer periods than their peers. When this emotional drive of necessity doesn’t exist, no tactic, tool, or strategy can help them.

If I’ve learned anything from my research and

a decade of interventions developing high performers, it’s that

you cannot become extraordinary without a sense that

it’s absolutely necessary to excel.

You must get more emotionally committed to what you are doing, and reach that point where success (or whatever outcome you’re after) is not just an occasional preference, but a soul-deep necessity. This chapter is about how.

Necessity Basics

Necessity is the mistress and guide of nature. Necessity is the theme

and inventress of nature, her curb and her eternal law.

— Leonardo Da Vinci

These are the factors in performance necessity (which I call the Four Forces of Necessity): identity, obsession, duty, and urgency. The first two are mostly internal. The second two are mostly external. Each is a driving force of motivation, but together they make you predictably perform at higher levels.

The nuances of necessity are not always obvious, so we will spend a few moments on description before we move to prescription. Bear with me, because I’m betting you will identify some significant areas of your life where greater necessity can change the game.

[Design: Please insert the JPEG image titled “performance Necessity Venn diagram” on the Products drive. Here is the file path: L:\Products\H\High Performance Habits\hardcover\images.]

Internal Forces

Whatever I have tried to do in life, I have tried with all my heart to do it well;

whatever I have devoted myself to, I have devoted myself to completely.

— Charles Dickens

Have you ever noticed that you feel guilty when you’re not living your values or being the best version of yourself? Perhaps you believe you’re an honest person but feel you lie too often. You set goals but don’t follow through. Conversely, have you noticed how good you feel when you’re being a good person and following through on what you say and desire? Those feelings of being frustrated or happy with your performance are what I mean by internal forces.

We humans have a lot of internal forces shaping our behavior: your values; expectations; dreams; goals; and need for safety, belonging, congruence, and growth, to name but a few. Think of these internal forces as an internal guidance system that urges you to stay “who you are” and grow into your best self. They are forces that continuously shape and reshape your identity and behaviors throughout your life.

We’ve found that two specific internal forces—personal standards of excellence and obsession with a topic—are particularly powerful in determining your ability to succeed over the long term.

High Personal Standards and Commitment to Excellence

The quality of a person’s life is in direct proportion to their commitment

to excellence, regardless of their chosen field of endeavor.

— Vince Lombardi

It goes without saying that high performers hold themselves to a high standard. Specifically, they care deeply whether they perform well at any task or activity they see as important to their identity. This is true whether or not they choose the task. It’s also true whether or not they enjoy the task. It’s their identity—not always the choice or enjoyment of the task—that drives them to do well.1 For example, an athlete may not particularly enjoy a workout their coach has given them, but they do it because they see themselves as an elite athlete willing to try anything to get better. Organizational researchers have also found that people don’t perform well just because they’re doing tasks they’re satisfied with, but rather because they’re setting challenging goals that mean something to them personally.2 Satisfaction is not the cause of great performance; it’s the result. When we do what aligns with our future identity, we are more driven and likely to do a great job.

Naturally, we all want to do a good job on things that are important to us.

But high performers care even more about excellence

and thus put more effort into their activities than others do.

How can we know that they care more? Because they report self-monitoring their behavior and performance goals more often. High performers don’t just know that they have high standards and want to excel; they check in several times throughout their day to see whether they are living up to those standards. It’s this self-monitoring that helps them get ahead. In conducting hundreds of performance reviews, I’ve found that underperformers, on the other hand, are often less self-aware and sometimes oblivious to their behavior and their results.

These findings align with what researchers have found about goals and self-awareness. For example, people who set goals and regularly self-monitor are almost two and a half times more likely to attain their goals.3 They also develop more accurate plans and feel more motivated to follow through on them.4 In one review of 138 studies spanning more than 19,000 participants, researchers found that monitoring progress is just as important to goal attainment as setting a clear goal in the first place.5 If you’re not going to monitor your progress, you may as well not set a goal or expect to live up to your own standards. This applies to almost all aspects of our lives, even the mundane ones. Imagine you envision yourself as a healthy person and you want to lose a few pounds. If you don’t set a goal and track your progress, you’re almost sure to fail. One meta-analysis found that self-monitoring was among the most effective means for improving weight loss results.6

So how does this relate to high performance? You need some sort of practice for checking in on whether you are living up to your own personal standards. This can be as easy as journaling every night and considering this line of questioning: “Did I perform with excellence today? Did I live up to my values and expectations for giving my best and doing a good job?”

Asking yourself these kinds of questions daily can bring up tough truths. No one is perfect, and inevitably you’ll have days when you aren’t proud of your performance. But that’s part of the deal. If you don’t self-monitor, you’ll be less consistent and will advance more slowly. And if you do self-monitor, you may still feel frustrated from time to time. That’s just how it goes.

High performers can certainly be hard on themselves if they don’t perceive growth or excellence in what they’re doing. But this does not mean they’re unhappy or are turning into neurotic stress cases who always feel that they’re failing. Remember the data: high performers are happier than their peers, perceive that they have less stress than their peers, and feel that they’re making a greater difference and are being well rewarded for those efforts. They feel this way because they feel that they’re on the right path. And they feel that they’re on the right path, because they frequently check in with themselves.

In every discussion I’ve had with high performers, I’ve found them more than willing to face their faults and address their weaknesses. They don’t avoid the conversation. They don’t pretend to be perfect. Indeed, they want to talk about how to improve, because at their core, their identity and enjoyment in life are tied to growth.

So how can high performers look themselves in the mirror so often and not get discouraged? Perhaps it’s simply because self-evaluation is something they’re used to. They’re comfortable with it. They don’t fear observing themselves, flaws and all, because they do it so often. The more you do something, the less it stings.

Still, high performers can be tough on themselves when they fail, because excellence is so important to their identity. When your identity says, “I’m someone who gets things done and does them with excellence,” or “I’m a successful person who cares about the details and how things turn out,” then you care when things go sideways. To high performers, those statements aren’t just affirmations but an integral part of who they are. This means there is real internal pressure to do well, and that pressure can be hard to tame or turn off.

And, of course, if high performers aren’t careful, these high standards can backfire. We can become too critical of ourselves, and soon self-evaluation begins to equate with pain. When that happens, either we stop asking whether we’re doing things with excellence (because the answer is too painful) or we keep asking and psyche ourselves out. Over-concern with making mistakes increases anxiety and decreases performance.7 When a star golfer suddenly chokes on the eighteenth hole, it’s not because they lack the necessity to do well. It’s that they allowed necessity to generate a debilitating level of expectation and pressure.

Still, choking is surprisingly rare for high performers because, again, they’re so used to dealing with high necessity.8

It’s important to consider our findings on low performers. They report self-monitoring only a third to half as many times per week as their high performing peers. And they rarely agree strongly with statements such as “I have an identity that thrives on seeking excellence, and my daily behaviors show it.” Perhaps an identity of excellence is just too risky. If you regularly feel bad about yourself because you are underperforming, then naturally you might prefer to avoid self-evaluation. But this becomes the ultimate irony for underperformers: if they don’t self-monitor more, their performance won’t improve. And yet, if they do self-monitor more, they’ll have to deal with the inevitable disappointments and self-judgments.

The goal for all underperformers must be to set new standards,

self-monitor more frequently, and learn to become comfortable

with taking a hard, unflinching look at their own performance.

I don’t pretend that it’s an easy task. Avoiding potentially negative emotions is a deeply ingrained human impulse. I’m not blind to the fact that feeling intense necessity isn’t always rainbows and roses. Striving to play at your best in any area of life can make you truly vulnerable. It’s scary to demand a lot of yourself and push to the boundaries of your capabilities. You might not do a good job. You might fail. If you don’t rise to the occasion, you can feel frustration, guilt, embarrassment, sadness, shame. Feeling that you have to do something isn’t always comfortable.

But I suppose that’s the ultimate tradeoff high performers make. They sense they must do something with excellence, and if they fail and have to endure negative emotions, so be it. They too highly value the performance edge that come from necessity to let themselves off the hook. The payoff is worth the potential discomfort.

Don’t fear this concept of necessity. Lots of people are leery of the idea when I introduce it to them. They fear they’re not enough or can’t handle the hardship of real demands. But necessity doesn’t just mean something “bad” happened and you now you “have to” react. It doesn’t mean the demand is a negative load to bear.

This is why I often tell low performers:

Sometimes the fastest way to get back in the game

is to expect something from yourself again.

Go ahead and tie your identity to doing a good job. And remember to set challenging goals. Decades of research involving over forty thousand participants has shown that people who set difficult and specific goals outperform people who set vague and non-challenging goals.9

See yourself as a person who loves challenge and go for the big dreams. You are stronger than you think, and the future holds good things for you. Sure, you might fail. Sure, it might be uncomfortable. But what’s the alternative? Holding back? Landing at the tail end of life and feeling that you didn’t give it your all? Trudging through life safely inside your little bubble bored or complacent? Don’t let that be your fate.

High performers have to succeed over the long term because they have the guts to expect something great from themselves. They repeatedly tell themselves they must do something and do it well because that action or achievement would be congruent with their ideal identity.

High performers’ dreams of living extraordinary lives aren’t mere wishes and hopes. They make their dream a necessity. Their future identity is tied to it, and they expect themselves to make it happen. And so they do.

Obsession with Understanding and Mastering a Topic

To have long-term success as a coach or in any position of leadership,

you have to be obsessed in some way.

—Pat Riley

If an internal standard for excellence makes solid performance necessary, then the internal force of curiosity makes it enjoyable.

As you would expect, high performers are deeply curious people. In fact, their curiosity for understanding and mastering their primary field of interest is one of the hallmarks of their success. It’s truly a universal observation across all high performers. They feel a high internal drive to focus on their field of interest over the long term and build deep competence. Psychologists would say they have high intrinsic motivation—they do things because those things are interesting, enjoyable, and personally satisfying.10 High performers don’t need a reward or prod from others to do something, because they find it inherently rewarding.

This deep and long-term passion for a particular topic or discipline has been noted in almost all modern success research. When people speak of “grit,” they’re talking about combined passion and perseverance. If you’ve heard of “deliberate practice”—often misinterpreted as the ten-thousand-hour rule—you know that it matters how long you focus on and train for something. The findings are straightforward. People who become world-class at anything focus longer and harder on their craft.

But I’ve found that high performers must have something more than just passion. Passion is something everyone can understand. It’s acceptable. We’re told to be passionate, live with passion, love with passion. Passion is the expectation, the first door to success. But if you can stay highly emotionally engaged and laser focused over the long term, even when motivation and passion inevitably rise and ebb in waves of interest, even when others are criticizing you (and you know they might be right), even when you fail again and again, even when you are forced to stretch well beyond your comfort zone so that you can keep climbing, even when the rewards and recognition come too far apart, even when everyone else would have given up or moved on, even when all signs say you should quit—that’s a leap beyond grit into the territory of what many might call an irresponsible obsession. It borders on recklessness. I took up this point in The Motivation Manifesto:

Our challenge is that we have been conditioned to believe the opposite of these things—that bold action or swift progress is somehow dangerous or reckless. But a certain degree of insanity and recklessness is necessary to advance or innovate anything, to make any new or remarkable or meaningful contributions. What great thing was ever accomplished without a little recklessness? So-called recklessness was required for the extraordinary to happen: crossing the oceans, ending slavery, rocketing man into space, building skyscrapers, decoding the genome, starting new businesses, and innovating entire industries. It is reckless to try something that has never been done, to move against convention, to begin before all conditions are good and preparations are perfected. But the bold know that to win, one must first begin. They also deeply understand that a degree of risk is inevitable and necessary should there be any real reward. Yes, any plunge into the unknown is reckless—but that’s where the treasure lies.

Am I mincing words here? No—this is what high performers worldwide spoke with me about.

When you are passionate about what you do, people understand.

When you are obsessed, they think you’re mad. That’s the difference.

It is this almost reckless obsession for mastering something that makes us feel the imperative to perform at higher levels.

In any field of endeavor, those lacking obsession are often easy to spot: the half-interested browsers, the halfhearted lovers, the half-engaged leaders. They may lack intense interest, passion, or desire in general. But not necessarily. Sometimes, they have lots of interests, passions, and desires. But what they lack is that one thing, that abiding and unquenchable obsession. You know within minutes of meeting someone whether they have an obsession. If they have it, they’re curious, engaged, excited to learn and talk about something specific and deeply important to them. They say things like “I love doing what I do so much, I’m sort of obsessed.” Or “I live, eat, and breathe this; I can’t imagine doing something else—this is who I am.” They speak enthusiastically and articulately about a quest for excellence or mastery in their field, and they log the hours of study, practice, and preparation to achieve those ends. Their obsessions land on their calendars in real work efforts.

The moment you know that something has transcended being a passion and has become an obsession is when that something gets tied to your identity.

It changes from a desire to feel a particular state of emotion—passion—

to a quest to be a particular kind of person. It becomes part of you, something

you value more deeply than other things. It becomes necessary for you.

Just as some people fear setting high standards for themselves, many fear becoming obsessed. They prefer casual interests and passing flames. It’s easier to live with passions that have no stake in who you are.

It’s worth the reminder: high performers can handle this sort of internal pressure. They don’t mind diving into the deep end of their passions. Obsession is not something to fear. Quite the contrary. It’s almost like a badge of honor. When people are obsessed with something, they enjoy doing it so much that they don’t feel the need to apologize to others for it. They lose hours working at a task or improving a skill. And they love it.

Are there “unhealthy” obsessions? I suppose that depends on how you define things. If you get so enthralled by something that you become addicted or think about it compulsively, then yes. That’s not exactly healthy. If you define an obsession as a “persistent disturbing preoccupation,” as Merriam-Webster does for one sense of the word, then yes, taking it to the degree of “disturbing” is probably unhealthy. But the dictionary also defines obsession in these ways:

- a state in which someone thinks about someone or something constantly or frequently, especially in a way that is not normal

- someone or something that a person thinks about constantly or frequently

- an activity that someone is very interested in or spends a lot of time doing

- a persistent abnormally strong interest in or concern about someone or something

I don’t find any of those senses of the word particularly unhealthy. So again, it depends on the definition you choose. What I know about high performers is that they do indeed spend an enormous amount of time thinking about and doing their obsession(s). Is this “abnormal”? Absolutely.

But normal isn’t always healthy, either.

Let’s be honest: a normal amount of time spent on almost anything in today’s distracted world is about two minutes. So, if an abnormal amount of focus is “unhealthy,” then high performers are guilty as charged. But I don’t observe high performers as being unhealthy—and I spend more time observing them than just about anyone does. If you’re wondering whether you have an unhealthy obsession, it’s pretty easy to figure out: when your obsession starts running you instead of you running it, if it starts tearing up your life and wrecking your relationships and causing unhappiness all around, then you’ve got a problem.

But that’s just not a problem high performers have. Otherwise, by definition, they wouldn’t be high performers. The data bears this out.12 High performers are happy. They are confident. They eat healthy amounts of healthy foods, and they exercise. They handle stress better than their peers. They love challenge, and sense that they’re making a difference. In other words, you could say they’re in control.

That’s why I encourage people to keep experimenting in life until they find something that sparks unusual interest. Then, if it aligns with your personal values and identity, jump in. Get curious. Let yourself dork out on something and go deep. Let that part of you that wants to obsess about and master something come alive again.

When high personal standards meet high obsessions, then high necessity emerges. So, too, does high performance. And that’s just the internal game of necessity. The external forces are where things really get interesting.

Before we move on to the external forces, spend some time reflecting on the following statements:

- The values that are important for me to live include . . .

- A recent situation where I didn’t live my values was . . .

- The reason I didn’t feel it necessary in that moment to live my values is . . .

- A recent situation in which I was proud of living my values or being a particular kind of person was . . .

- The reason I felt it necessary to be that kind of person then was . . .

- The topics I find myself obsessed with include . . .

- A topic I haven’t been obsessing about enough in a healthy way is . . .

External Forces

You never know how strong you are

until being strong is your only choice.

— Bob Marley

An external force of necessity is any outside factor that drives you to perform well. Some psychologists might simply describe this as “pressure.”13 I rarely use the term pressure, though, because it carries a lot of negative connotations. For the most part, high performers don’t feel ongoing unwanted pressures causing their drive for excellence. Like all of us, they have obligations and deadlines, but the distinction is that they consciously choose those duties and thus don’t see them as negative pressures to perform. They are not pushed to performance; they are pulled.

I used to get this wrong. In one of our pilot studies for the High Performance Indicator, we asked people to score whether they agreed strongly with this statement: “I feel an external demand—from my peers, family, boss, mentor, or culture—to succeed at high levels.” To my initial surprise, this statement didn’t correlate with high performance.14 In asking high performers about this result, I learned that the reason is because the demands they sense to succeed do not come from other people. If they do feel pressure from others in a way that makes them perform better, it likely just reinforces choices or behaviors they may already have committed to. Another way of saying this is that high performers don’t necessarily view external forces as negative things or as causal reasons for their performance.

This means that high performers are not functioning from what psychologist often call reactance, which are acts motivated by the will to fight back or act out against a perceived insult or threat. High performers’ necessity for action in life does not stem from wanting to fight “the system” or whoever is putting them down. High performers aren’t driven because they are rebelling or feeling threatened. That type of “negative” motivation certainly exists, but alone it rarely lasts long or accomplishes much.

More often, high performers view “positive” external forces as causal reasons for increased performance. They want to do well to serve a purpose they find meaningful—fulfilling a high purpose serves as a positive sort of pressure. Even obligations and difficult-to-meet deadlines—which many people dislike—are viewed as positive performance enhancers.

With this in mind, there are two primary positive external forces that exert the kind of motivation or pressure that improves performance.

Social Duty, Obligation, and Purpose

Duty makes us do things well,

but love makes us do them beautifully.

— Phillips Brooks

High performers often feel the necessity to perform well out of a sense of duty to someone or something beyond themselves. Someone is counting on them, or they’re trying to fulfill a promise or responsibility.

I define duty broadly because high performers do, too. Sometimes, when they speak of duty, they mean that they owe something to others or are accountable for their performance (whether or not anyone has asked for the thing they feel obligated to do). Sometimes, high performers view duty as an obligation to meet another’s expectations or needs. Sometimes, they see duty as complying with the norms or values of a group, or following a moral sense of right and wrong.15

The duties that drive performance can be explained best by the truth that we will often do more for others than for ourselves. We’ll get up in the middle of the night to calm an upset child even though we know we need sleep. It’s just more necessary in our mind to do this thing for someone else. This type of necessity is often the strongest pull. So if you ever feel that you are not performing well, start asking, “Who needs me more right now?”

If you add to that accountability—when people know that you are responsible for helping them—necessity becomes stronger yet. A tremendous amount of research shows that people tend to maintain motivation, give more effort, and achieve higher performance when they are held accountable for their outcomes, are evaluated more often, and have the opportunity to demonstrate their expertise or gain respect from those they serve.16 In other words, if you owe it to someone to do well, and you feel that doing well will exhibit your expertise, then you’ll feel greater necessity to perform at higher levels. For example, when we are evaluated more and held accountable to team performance, we work harder and better.17

This all sounds nice, but we all know that often a sense of duty to others can feel like a negative thing in the short term. Few parents are eager to wake up in the middle of the night and change a diaper. Doing so is more an obligation than an expression of warmhearted love. Will parents complain about that obligation? Sure. But over the long term, adherence to meeting that “positive” obligation helps make them feel like good parents, which is at least part of what motivates them to do it. In other words, the external demands we feel to meet our obligations in life can feel bad in the short term but lead to strong performance outcomes later.

It’s hard for underperformers to see that obligations are not always a negative thing, which is why we found that underperformers complain more about their responsibilities at work than their high performing peers. Some obligations can naturally feel like something to complain about. A sense of obligation to family, for instance, might lead you to live near your parents or to send them money. This kind of familial duty might feel like a ball and chain to many, but meeting such duties also happens to correlate with positive well-being.18

At work, a sense of “doing the right thing” drives positive emotions and performance as well. Organizational researchers have found that employees who are the most committed, especially in times of change, feel that it would be “wrong” to leave a company if their absence would hurt the company’s future.19 They often double-down on their efforts to help their managers even though it requires longer work hours. Duty to the mission replaces their short-term comforts.

Because high performers understand the need to meet their obligations, they rarely complain about the tasks and duties they must perform to succeed. They recognize that fulfilling their role and serving the needs of others is part of the process. It’s a positive thing tomorrow even if it’s a pain now. It’s these findings that have inspired me to view my obligations in life differently. I’ve learned to adjust my attitude to things I have to do, to complain less and realize that most of what I “have” to do is in truth a blessing.

I learned that when you have the opportunity to serve,

you don’t complain about the effort involved.

When you feel the drive to serve others, you sustain solid performance longer. This is one reason, for example, why members of the military are often so extraordinary. They have a sense of duty to something beyond themselves—their country and their comrades in arms.

It’s also why most high performers mention “purpose” as motivating their best performance. Their sense of duty or obligation to a higher vision, mission, or calling propels them through the hardships of achievement.

In fact, when I talk with high performers, they regularly say they “don’t have a choice” but to be good at what they do. They don’t mean this as a lack of freedom, as if some autocratic leader were forcing them to do something. What they mean is, they feel that it’s necessary to do something because they’ve been called to do it. They feel they have been given a unique gift or opportunity. Often, they sense that their performance now will affect their future and, perhaps, the futures of a lot of people, in profound ways.

This sense of duty to a higher calling is almost ubiquitous when you talk to the top 15 percent of high performers. It is not rare to hear them talk about legacy, destiny, divine timing, God, or a moral responsibility to future generations as primary motivators for their performance. They need to perform well, they say, because they know they are needed.

Real Deadlines

Without a sense of urgency, desire loses its value.

— Jim Rohn

Why do athletes work out harder in the weeks immediately before walking into the ring or onto the field? Why do salespeople perform better at quarter’s end? Why do stay-at-home parents report being better organized right before school starts? Because nothing motivates action like a hard deadline.

Real deadlines are an underappreciated tool in performance management. We’d rather talk about goals and timelines, setting “nice to have” dates to achieve those goals. But high performance happens only when there are real deadlines.

What is a “real” deadline? It’s a date that matters because, if it isn’t met, real negative consequences happen, and if it is real, benefits come to fruition.

We all have deadlines in life. The distinction that matters here is that high performers seem to be regularly marching toward real deadlines that they feel are important to meet. They know the dates when things are due, and the real consequences and payoffs associated with those dates. But just as important, high performers are not seeking to meet false deadlines.

A false deadline is usually a poorly conceived activity with a due date that is someone’s preference, not a true need with real consequences if it’s not met. It’s what one of my clients, a Green Beret, calls a “circle jerk fire drill.”

Here is how this distinction between real and fake deadlines plays out in my life. Whenever someone e-mails me a request, with or without a due date, I reply in this way:

Thanks for your request. Can you give me the “real deadline” date for this? That means the date when the world will explode, your career will be destroyed, or a domino effect leading to both your and my ultimate demise will truly begin. Any date before that is your preference, and with respect, by the time you’ve sent me this request I have 100 preference requests in front of you. So, to serve you best, I have to put you in ranking order with the real deadlines. Can you please let me know that drop-dead date and why, specifically, it occurs then? From there, I’ll decide the priority and coordinate appropriately with you and, as always, serve with excellence. Thanks!

—Brendon

I send this e-mail because I know how quickly I can fall out of high performance by meeting other people’s demands that aren’t real demands. I’m a people pleaser. I’m a sucker for distraction. Habits such as clarifying real deadlines are what make me, and every high performer I know, so effective.

A recent survey of 1,100 high performers revealed that their underperforming counterparts get pulled into fake urgencies or deadlines three and a half times more often than they do.20 They are more focused on doing what really matters when it matters.

But that’s not simply because high performers are superhuman and always focused on their own deadlines. In fact, for the most part, the real deadlines that high performers are marching to have been placed on them by others, by outside forces. Olympians don’t choose when the games will be held, and CEOs don’t set the quarterly demands thrust on them by the marketplace.

Left to my own devices, I probably would never have finished this book. But I knew that at some point, if I didn’t turn it in, my family would mutiny, my friends would abduct me, and my publisher would dump me. Sure, I missed a few false deadlines, which I had set. But once there was a real deadline, when my publisher promised the book to retailers, and my wife expected a vacation, bam, the words per hour increased exponentially.

This isn’t to say that high performers are driven to meet a deadline only by the negative consequences of missing it. In fact, most want to meet their deadlines because they’re excited to see their work out there in the world, as well as to move on to the next project or opportunity they have chosen for themselves. I was eager to finish this book not just because I feared the negative repercussions of being late; I was also excited to finish so I could get the book in your hands and turn more of my attention to my family and to reaching more students with this message.

This example illustrates another aspect of real deadlines: that they are inherently social deadlines. High performers are driven to get things done because they recognize that their timeliness affects other people.

The reality is that when you choose to care for others

and make a big difference in the world,

the number of deadlines coming at you will increase.

Some might assume that time pressure makes people miserable. But that’s just not what I’ve observed or what other research is finding. A recent study found that by having a deadline, not only did people focus more to complete the activity but they found it easier to “let that activity go” and devote greater attention to the next activity.21 That is, deadlines help us get closure between activities, so we can give our full focus to what we need to be working on now.

Keeping the Fire

Identity. Obsession. Duty. Deadlines. As you can imagine, any one of these forces can make us bring up our game. But when internal and external demands mix, you get more pressure, and an even stronger wind at your back.

I’ll repeat the part about this being a sensitive topic. Lots of people really dislike necessity—they hate feeling any sort of pressure. They don’t want internal pressure because it can cause anxiety. And they don’t want external pressure because it can cause anxiety and real failure. Still, the data is clear: high performers like necessity. In fact, they need it. When it’s gone, their fire is gone.

For an example of how this might play out, imagine you’re working with someone who is in the top 2 percent of high performers. They say to you, “I feel like I’m not as consistent or as disciplined as I used to be.” What would be your next move with them? Would you make them take a personality test or a strengths assessment or go to a retreat in the woods?

I sure wouldn’t. I’d have a real conversation with them about necessity. I’d find out about a time when they did feel consistent, and I’d explore the Four Forces of Necessity with them to see what led them to such impressive performance in the past. Then I’d cycle through the Four Forces again, seeking to get the high performer more deeply connected to their hunger for achievement because of their identity, obsessions, and sense of duty and urgency. If they didn’t have something they felt obsessed with, obligated to, or at risk of losing or missing out on, I’d have them find something to care deeply about. I wouldn’t let them off the hook until we were clear about the Four Forces.

This is exactly what I did with Isaac, the soldier struggling with the feeling that he wasn’t useful anymore. I got him to imagine his future in a new way, reconnect with some of the obsessions he had before his injuries, and commit to improving his health and mindset for his family and so he could get back to work. It wasn’t easy, but eventually Isaac reconnected with himself and again found his enthusiasm for life.

Bottom line: We change and improve over time only when we must. When the internal and external forces on us are strong enough, we make it happen. We climb. And when it gets most difficult, we remember our cause. When we are afraid and battling hardship and darkness, we remember we came in the cause of light and we sustain positive performance over the long term. Here are three practices that can fire up a greater sense of necessity.

…. read the rest of the chapter for the 3 PRACTICES that lock in this habit of necessity.